Μάθημα ένα (Mathima Ena)

Lesson 1

History of the Greek language

The earliest records of written Greek are inscribed on mud tablets found at the beginning of the present century in the ruins of the

The earliest inscriptions in the forerunner of today's Greek alphabet date from about 750 B.C., long after the Mycenaeans, mainland successors to the Minoans and heroes of the Trojan war, had declined in influence and at about the time the poet Homer is said to have lived.

When considering ancient

Bearing in mind that while Homer flourished in the 8th century B.C. (and some of his language was archaic even for that period) and Aristotle did not die until 322 B.C., not only do the texts popularly associated with ancient Greek writing span a considerable period of time (at least equal to the period between the present day and Shakespeare) but are composed in a number of distinct dialects. There is thus, at least in one sense, no such thing as standard ancient Greek common to all speakers - although maybe one such candidate did emerge. During the classical period

However politics were soon to bring about further and more radical change to the Greek language. Philip II of Macedon (382 - 336 B.C.) followed by his yet more ambitious son, Alexander the Great (356 - 323 B.C.), swept away the traditional city states, uniting

It may be supposed that when the Romans arrived in

It was not until the uprising against the Turks in 1821 that the modern Greek state was born. However this did not stop Greek intellectuals of the eighteenth century dreaming about the institutions of an independent Greece, in particular the language that was, together with Orthodox Christianity, to be one of the unifying factors of the new nation. Reinventing a language may today seem a rather pointless occupation but to the Greeks of the late 18th century plotting revolution against the Ottoman Turks, there were important practical questions to be resolved. Although a tradition of Greek literature had been maintained through the years of occupation by Frank, Venetian and Turk, this had been achieved mainly through the flowering of isolated centres of culture over relatively brief periods (e.g. Crete during the 16th & early 17th centuries and later in the Ionian islands after the fall of

Needless to say, even from the earliest days, not everyone was happy with this middle way. Some thought the proposed reforms had not gone far enough while others, particularly literary writers, thought katharevousa was too remote from the speech of the common people. It was not long before an alternative was proposed, adapting and systematizing the common spoken language of the people, demotiki (demotic Greek). The debate between proponents of these two approaches was fierce; academics were sacked for using demotiki and the language question even led to rioting in the streets. In the twentieth century the language debate took on a political significance with social reformers claiming that katharevousa was being used as an instrument to deny the common man access to education and advancement while nationalist governments generally tended to favour katharevousa.

The battle was finally won as recently as 1976 with the adoption of demotiki as the language of education and administration. Katharevousa is still sometimes encountered in legal texts but its demise will no doubt be spurred by the fact that classical Greek is no longer widely taught in Greek schools. There is a now a reasonable, if not perfect, consensus on what comprises "good" Modern Greek based largely on demotiki but not averse to the occasional inclusion of a katharevousa phrase where tradition or common sense would justify it. For example, the ancient word for "house" is οίκος (Which is the root of words like economy and ecology). A publishing house in Greek is called εκδοτικός οίκος and a fashion house is called οίκος μόδας. When you are talking about a house in general though, you will use the demotic word σπίτι and not the word οίκος.

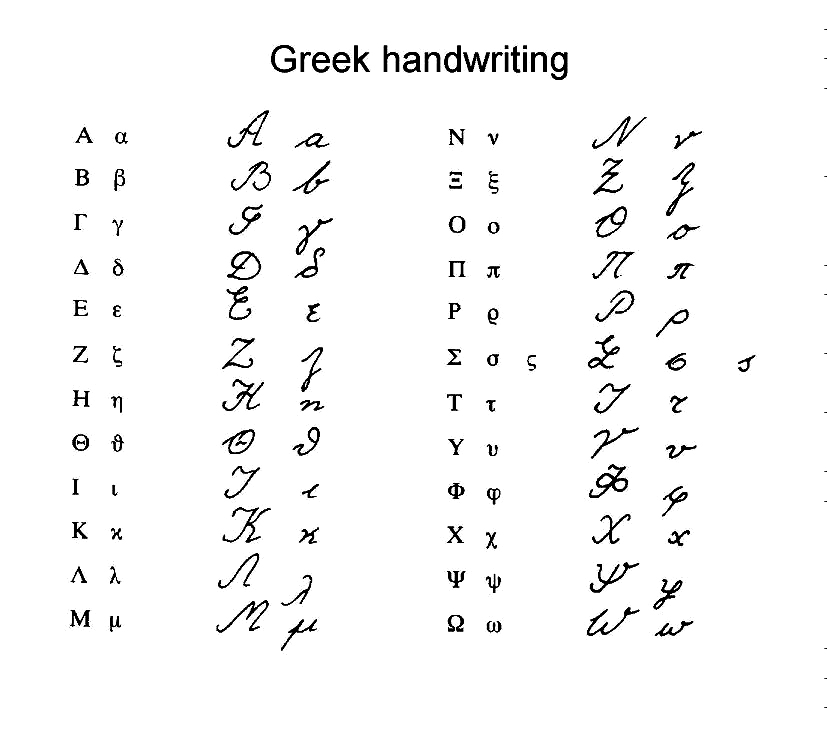

The alphabet - Το αλφάβητο (to alfavito)

Alpha is the first letter, Beta the second and so starts the Greek alphabet, 24 letters in capital and small forms; (cf. detailed pronunciation below):

Αα, Ββ, Γγ, Δδ, Εε, Ζζ, Ηη, Θθ, Ιι, Κκ, Λλ, Μμ, Νν, Ξξ, Οο, Ππ, Ρρ, Σσς*, Ττ, Υυ, Φφ, Χχ, Ψψ, Ωω.

*Note that σ is written as ς at the end of a word, e.g. σός (=yours) and is called final sigma. In Byzantine Greek you will also find Σ written as C.

*Note that the Greek P is the English R (this is how it sounds). What in English is P in Greek is Π.

*Note that H in Greek is a vowel, corresponding to the English E. Don't confuse it's small version η with the English n. The English n in Greek is ν.

*Don't confuse ν with the English v. The English v in Greek is β.

There are two more sounds in older Greek, that became useless. The one corresponded to the letter F and was called "Digamma", since it was like two Γ. It sounded like 'wo'. The other was a sound like y in the word year. There was no letter for this sound, but to refer to it today we use the latin j.

|

Ωω (ome/ga) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here is the pronounciation of the greek letters:

Α α (Άλφα) as in Anna

Β β (Βήτα) as in vase

Γ γ (Γάμμα) as in yes

Δ δ (Δέλτα) as in this

Ε ε (Έψιλον) as in Helen

Ζ ζ (Ζήτα) as in zone

Η η (Ήτα) as in feet

Θ θ (Θήτα) as in thistle

Ι ι (Γιώτα) as in feet

Κ κ (Κάπα) as in cake (but softer)

Λ λ (Λάμδα) as in limp

Μ μ (Μι) as in mother

Ν ν (Νι) as in no

Ξ ξ (Ξι) as in axe

Ο ο (Όμικρον) as in on

Π π (Πι) as in party (but softer)

Ρ ρ (Ρο) as in room

Σ σ ς (Σίγμα) as in sister (ς is used instead of σ at the end of words)

Τ τ (Ταύ) as in tonight (but softer)

Υ υ (Ύψιλον) as in feet

Φ φ (Φι) as in fire

Χ χ (Χι) as in he

Ψ ψ (Ψι) as in lapse

Ω ω (Ωμέγα) as in on

Double vowels:

αι as in Helen

οι, ει, υι as in feet

ου as in fool

ευ as in left

ευ as in ever

αυ as in after

αυ as in avoid

Double consonants:

γγ, γκ as in go

ντ as in dog

μπ as in bat

τσ as in cats

τζ as in Jack

The Basics

Hello (Ya-soo) |

|

Hello (Ya-sas) |

|

Good morning (Ka-li-mera) |

|

Good afternoon (Hai-re-te) |

|

Good evening (Ka-li-spera) |

|

Goodnight (Ka-li-nik-ta)(you may have noticed that 'Kal-li' means 'good') |

|

Thank you (Ef-hari-sto)

(a little bit difficult - you will need some practice!) |

|

Yes (N-e)(notice that the ending is very short) |

|

No (O-chi) |

|

Please (Para-kalo) |

|

Tomorrow (Av-rio) |

|

Alright / OK (En-daxi) |

|

How are you? (Ti kan-e-te) |

|

Expensive! (Ak-ri-vo) |

|

Do you speak English? (Mi-la-te An-gli-ka) |

|

I do not speak Greek (Then mi-la-o El-i-ni-ka) |

|

I speak a little Greek (Mi-lao li-go E-lli-nika) |

|

Where are the toilets? (Pu i-ne i tua-let-tes) |

|

What time is it? (Ti ora i-ne) |

|

The articles

The definite article (the)

In Greek, nouns have 3 genders: masculine, feminine and neuter. Although the endings of nouns (and adjectives) are often indicative of their gender, a more certain way of identifying them is by their definite article:

ο for masculine nouns

η for feminine nouns

το for neuter

For example:

the man = ο άντρας (o antras)

the woman = η γυναίκα (i gineka)

the car = το αυτοκίνητο (to aftokinito)

Something that you should note is that in Greek we use articles before names, cities, countries etc. too. In English you would never say something like "The Chris" but in Greek you will say "Ο Χρήστος", or you would never say "The Greece" but in Greek you will say "Η Ελλάδα".

The indefinite article (a, an)

ένας (enas) masculine

μία (mia) feminine

ένα (ena) neuter

The indifinite article is also a good guide to the gender of a greek noun or adjective.

a man = ένας άντρας (enas antras)

a woman = μία γυναίκα (mia gineka)

a car = ένα αυτοκίνητο (ena aftokinito)

The plural definite article

Both the definite and indefinite articles decline just as nouns do (we'll talk about this later) and the definite article also has both a singular - for one object or person - and a plural - for more than one.

the man = ο άντρας (o antras) the men = οι άντρες (i antres)

the woman = η γυναίκα (i gineka) the women = οι γυναίκες (i ginekes)

the car = το αυτοκίνητο (to aftokinito) the cars = τα αυτοκίνητα (ta aftokinita)

Accentuation

In 1982 the system of accentuation was simplified to just one accent. Before that, there were 2 breathings and 3 different accents, which were similar to the French ones.

All words with more than one syllable (there are some exceptions but we will deal with them later) have an accent, which indicates the syllable to be read with extra emphasis. The position of an accent is important in establishing the meaning of words. Not infrequently the only distinguishing mark between two words, otherwise identical but with two different meanings, is the accent. For example consider the word γερος. If the accent goes to the epsilon (γέρος) we have a noun which means "old man". If the accent goes to the omicron (γερός) we have an adjective meaning "strong" or "tough".

A useful rule to remember for longer words is that a Greek word can have an accent only on one of the last three syllables.

I should also indicate how to put the accents on words in the computer. When you have switched to Greek keyboard, in order to place an accented letter, press the ; button and then after it the vowel you want to accent. For example, if you want to type the word γερός that I used above, you should press g (for γ), e(for ε), r (for ρ), ; and then o (for ό) and w (for ς). When we write in full capitals we don't use accents but when we have the first letter of a sentence (which means that it must be a capital followed by small letters) we accentuate it. For example, if you write the word Ενας, it should be like this: Ένας. To accentuate the E, you press ; and then Symbol shift with E to create the capital letter.

If you press ' (the button next to ;) and then the vowels i or u, the diairesis symbol comes up (ϊ ϋ), which I will discuss below (I have enlarged the fonts so that you can clearly see the diairesis symbol). For an accented diairesis, you should press Symbol shift and ; and then i or u (ΰ ΐ). The reason I mentioned only ι and υ is because the diairesis symbol is used only with these two vowels, while the accent symbol is used with all vowels (ά έ ή ί ό ύ ώ).

The diairesis rule

As I already mentioned, when the letters αι are next to each other like this, they should be read as ε. There are some exceptions to this rule however.

1)The accent is placed on the first vowel of the two, e.g. consider the word τσάι (tea). According to the general rules you would try to pronounce that as tse but because of the accent on top of the α, the correct pronounciation is tsa-i. So when you have any of the two-vowel combination, if the accent is on the first vowel, each vowel keeps its indivindual sound. If the accent is on the second vowel or there is no accent on any of the two vowels, it keeps the combined sound, unless:

2)The second vowel has the diairesis symbol ( ¨ or ΅ ) over it. The word διαίρεση means division, and that's what this symbol does, it divides the sound bvetween the two vowels. For example, we have the word γαϊδούρι (donkey). The diairesis over the ι means that it should be pronounced separately from the α, like that: ya-i-dhou-ri. Now, it may happen that the ι is accented, so we use diairesis with accent, like in the word φαΐ (food), which reads as fa-i. The diairesis can also be used with εϊ, οϊ, υϊ, αϋ, εϋ. But as I say again, this is an exception, 90% of the times you encounter a word which has αι together, it should be read like ε and so on for the other two-vowel combinations. Don't trouble yourself too much with the diairesis as it is used very rarily.

Vocabulary

January = Ιανουάριος or Γενάρης (ianuarios or Genaris)

February = Φεβρουάριος or Φλεβάρης (Fevruarios or Flevaris)

March = Μάρτιος or Μάρτης (Martios or Martis)

April = Απρίλιος or Απρίλης (Aprilios or Aprilis)

May = Μάιος or Μάης (Maios or Mais)

June = Ιούνιος or Ιούνης (iunios or iounis)

July = Ιούλιος or Ιούλης (iulios or ioulis)

August = Αύγουστος (Avgustos) (The Αύ is pronounced as Αβ)

September = Σεπτέμβριος or Σεπτέμβρης (Septemvrios or Septemvris)

October = Οκτώβριος or Οκτώβρης (Oktovrios or Oktovris)

November = Νοέμβριος or Νοέμβρης (Noemvrios or Noembris)

December = Δεκέμβριος or Δεκέμβρης (Dekemvrios or Dekemvris)

Note: All months are masculine so we say: ο Ιανουάριος, ο Μάης, etc...

Simple useful words:

yes = ναι (ne)

no = όχι (ohi)

and = και (ke)

or = ή (Note that the definite article η has no accent, but ή meaning "or" does have an accent, in order to distinguish the 2 words)

but = αλλά (alla)

maybe = ίσως (isos)

today = σήμερα (simera)

tomorrow = αύριο (avrio) (the αύ is pronounced as αβ)

yesterday = χτες (htes)